Defying the conventions of an ultra-conservative past, a young anthropologist has set out to normalise wearing saris in Pakistan

The ssari as Protest

Poetry and protest have long gone hand in hand around the world, and Pakistan is no exception. Ask any baby boomer about General Zia Ul-Haq’s regime, and they'll recall that night in 1985 when singer Iqbal Bano donned a black sari and sang Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s poem “Hum Dekhenge” at Alhamra Arts Council in Lahore. What sounds like an ordinary performance was actually a radical act of defiance, as Zia had essentially prohibited women from wearing saris—they were dubbed inappropriate—and banned the public recitation of Faiz’s often-revolutionary lyrics.

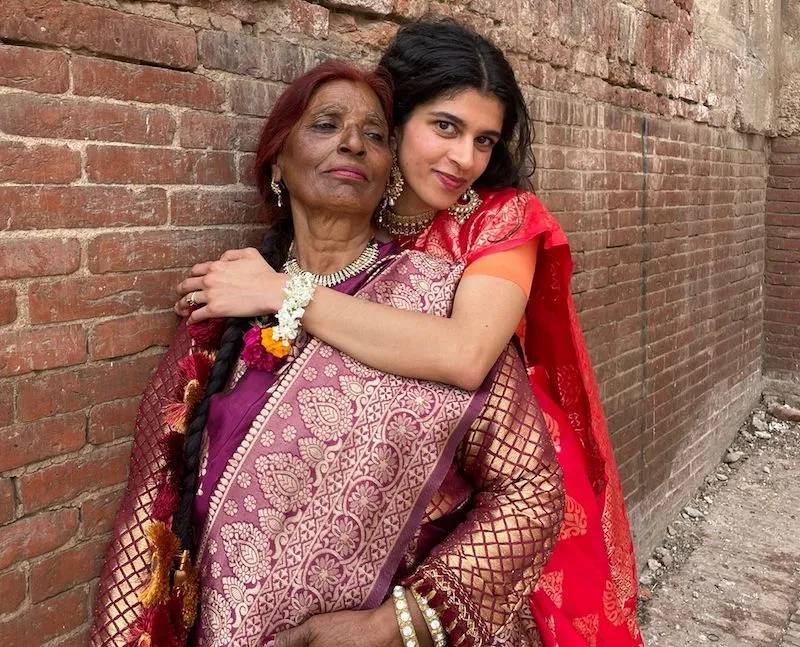

“Iqbal Bano simply wearing a sari was considered rebellious, indicating just how purposefully the dress had been sidelined,” says Aiza Hussain of that momentous event. The 26-year-old is the founder of The Saari Girl, a Lahore-based clothing brand rooted in the normalising of Pakistani women wearing saris. While this South Asian garment (a long, unstitched piece of cloth that's wrapped around the waist, then draped over the shoulder) is commonly worn across India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, it fell out of favour in Pakistan for various reasons—all of which Hussain, a sociocultural anthropologist by profession, set out to understand.

The Disappearing Saari

The sari has been left off lists of national Pakistani dress forms, and Aiza Hussain wants to know why

“Where has the sari gone?” she asked back in 2018, on the lookout for something “different” to wear. “It was for a Dean's Honour List dinner. I decided to wear a sari, but struggled to find options. I wanted something semi-formal, not too heavily embellished, and contemporary yet traditional. But practically everything I found was in India. And if I did find something locally, it was drastically more expensive than what was available across the border,” she recalls. “The range of designs was really limited, too. It was mind-boggling.”

Where has the sari gone?, she asked back in 2018"

Hussain may have ended up wearing a traditional shalwar kameez to that dinner, but the anthropologist in her wasn't satisfied. “I've always been interested in understanding social norms, their constructs, their deconstructs, so the questions kept coming. The partition happened in 1947, but it's not like there was a partition of dress forms. It does seem that way for most of the country, though—we have let go of the sari.”

Observing that the garment has only survived in select circles—the elite of Karachi, the Hindu community of Sindh, and what's left of the Parsi community—Hussain kickstarted the journey that eventually led to the creation of her brand and the first online sari store in Pakistan.

“I was conducting research, browsing local markets, talking to designers, and trying to figure out if launching cost-effective saris was even possible. What didn't make sense, though, was how easy it is to find budget-friendly shalwar kameez,” she says. “I mean, they have such similar measurements in terms of fabric needed, so why does a sari cost three times more?”

Policing Women's Bodies

What Hussain did not expect in this process, however, was the type of conversations she ended up having with women. While many expressed an interest in saris casual enough to be worn to lunch or a small gathering, several made confessions about their insecurities.

Saris can be worn for any occasion, be it casual or formal

"There were so many negative connotations attached to the sari, and that became the driving force behind my work"

“It would often turn into a therapy session with women who lacked body confidence, who had heard a lot of negative comments about their appearance. Some had husbands or even mothers-in-law who directed how they dressed,” she reveals, exasperated. “I learned a lot about the policing of women's bodies and, as a woman, I could relate. But the scale at which I was hearing these accounts? I cannot put it into words. ‘I have back acne.’ ‘My arms are too fat.’ ‘My husband doesn't like such colours on me.’ ‘My mother says it's not modest enough.’ There were so many negative connotations attached to the sari, and that became the driving force behind my work.”

The sari didn't just lose its appeal organically, she says, citing ownership as part of the reason it disappeared. “Most of us have ‘othered’ this garment. We think it’s linked to a particular religion, which brings with it a lot of stigma,” she says, explaining the widespread association between the sari and Hinduism. “Yes, stigma is a strong word, but based on my conversations, I can confirm that the sari is still stigmatised in many spheres within Pakistan. And I wouldn't hesitate to say that the Islamisation under Zia is partly to blame.”

Erasing culture

Incidentally, the shalwar kameez, dhoti, gharara, and lehenga are all listed as national dress forms in social studies textbooks, but not the sari. “This way, you erase a part of your own culture,” remarks Hussain. “Such decisive moves then carry over into billboards, brand advertisements, and magazines.” The Saari Girl may be a clothing brand, but influencing fashion is not at the top of Hussain's priorities. “I want to make women comfortable wearing the sari because it’s an element of our heritage.” Today, one glance at the brand's website proves that saris can be styled in a variety of ways for all body types.

Different saaris for different occasions

Saris are considered precious heirlooms, passed down through the generations

Some are minimalist in aesthetic, others are ornate and intended for special occasions. And they fall along a spectrum of modesty, a deliberate move on Hussain's part. “We want to illustrate that you can wear a sari with a hijab or a sleeveless blouse that has a low-cut neckline—both look beautiful. It's just a matter of how you want to style it because it doesn't have anything to do with religion. Look at Bangladesh; it's a Muslim-majority country where the sari has always been worn. In Pakistan, the problem lies in how we've constructed our culture and, by reviving the dress, our aim is to break the stereotypes around it.”

Past Pakistan's borders, a growing fascination with this fluid garment has translated to The Saari Girl creations reaching the likes of Australia, America, Germany and the UK. “A lot of our customers are based in the West,” reveals Hussain. “We get a lot of support from the Pakistani diaspora as well as Indians abroad, who are curious to see what the sari looks like for Pakistanis. It makes for an interesting cultural exchange. What surprised me most, though, was the group of young Turkish women who ordered saris to wear to a wedding.”

"The problem lies in how we've constructed our culture and, by reviving the dress, our aim is to break the stereotypes around it"

Understandably, Hussain can't help but wax lyrical about the sari's appeal. “A sari is an investment as it won't go out of style. It’s also something that you can share with family members since it's one size fits all—we’re talking about six metres of loose fabric that can be draped as you like. And when handled properly, it's an heirloom that can be passed on from generation to generation, making it an object that connects women with their mothers and grandmothers.”